INTERVIEW WITH NEDA RUZHEVA

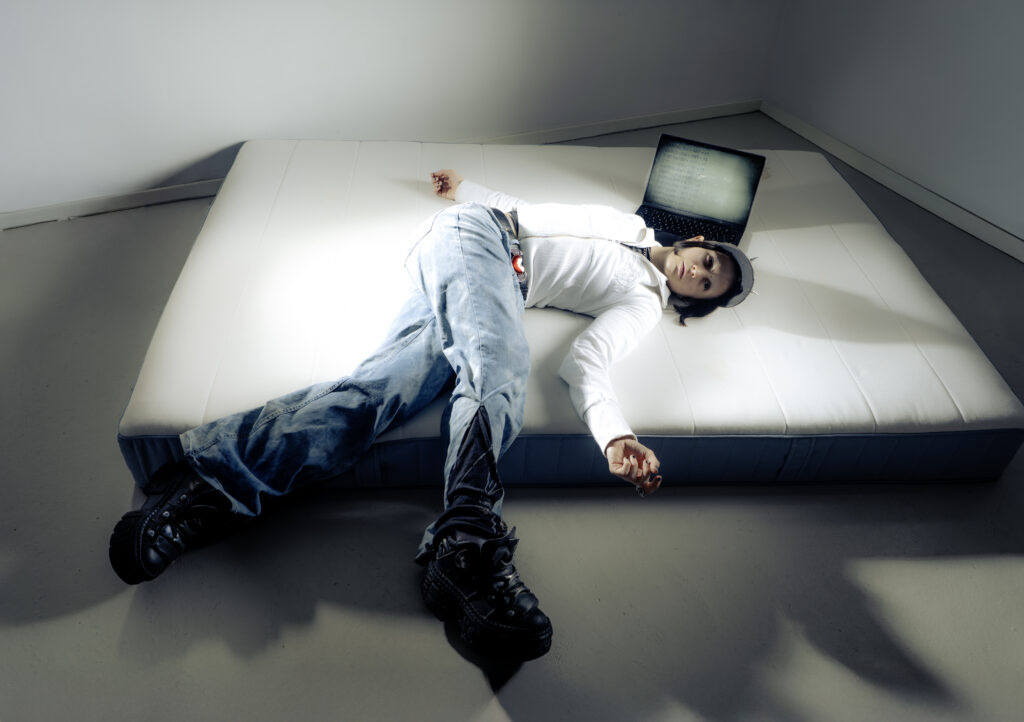

Neda Ruzheva, born in Sofia, Bulgaria, encountered contemporary dance at age 8. By 17, she was the youngest student ever admitted to the choreography program at the Academy of Theatre and Dance in Amsterdam. After graduating, she continued her studies at the Sandberg Institute and founded Trevoga in 2023 alongside a group of Eastern European artists, rejecting hierarchical dance models and embracing a horizontal, co-creative process.

Neda’s choreography blends academic rigor with subcultural grit. Her work fuses theory, sculpture, industrial sound, and intense physicality to probe the commodification of desire, the aesthetics of decay, and the longing buried beneath algorithmic alienation. Her trajectory—from Bulgarian break battles in her early youth to European mainstages—symbolizes a broader generational movement: to reclaim vulnerability as resistance, and to use the body as a site of critique and communion.

– How would you describe your artistic practice today? What are the primary themes and questions driving your current work?

A broken mirror of a broken present. Subjectivity is key for me. I get paranoid when I hear the body being referred to as something universal. I see myself as a symptom of the contexts I move through. My expression is their reflection — shaped by myths and contradictions. Always partial. Always incomplete. Always felt. +++ You never work alone in the theater, so it’s rather about the frictions and attractions of different worlds.

– Can you tell us about your collective Trevoga? I know that this word translates as fear and anxiety. Is there at the moment, more anxiety and fear in you than at the start of the project, or the opposite?

Trevoga is an intersection of performers who move against the flow. Dreamers. Doomers. Aliens. It means anxiety, as in rejecting escapism and coming face to face with the state of crisis of everything around. But it’s not about pessimism for the sake of it. That’s a kind of defense that doesn’t help anyone. It rather means that the future is unresolved – worth losing sleep over. I feel anxiety at every step of the process. I just gaslight myself that it’s arousal, pleasure in the pain of going through your shadow and coming out the other side.

– The referential aspect of your work is highly visible, especially references belonging to a newer Generation Z. Can you tell us who your primary audience is? Are millennials welcomed into your world?

I’m not sure these labels hold their shape anymore. Most Gen Z references are just millennial ghosts, distorted through distance and repetition. Symbols that have lost touch and become free-floating moods. And with the nichification of everything, the endless splitting into aesthetic cores, it’s almost impossible to decode each other even without a generational gap. So yes, millennials are welcome — everyone is. Affect over semiotics, any day

– Collaboration seems inherent to your craft. How do you find your crew?

There isn’t a simple formula. Some of us crossed by accident and instantly clicked. With others, we had been around each other for a while but hadn’t found that crossing point yet. A lot of us got connected through mutual friends. I really trust people around me to bring me to the right people. When I come up with a concept, it’s an open question; I look for people who know more than me or bring different angles.

– Can you please guide us through the development from your first performance 11 3 8 7 to the new performance? How was that road? What was that road?

I need to give context here. A lot of things changed in the dance scene this year; a lot of institutions had to close or reduce activities. 11 3 8 7 had a very comfortable upbringing — unlimited studio access, a devoted mentor, and administrative help. The new performance Xx-63, well, it’s as if your parents got evicted from their flat while you are still a baby. Don’t get me wrong, we had some amazing opportunities — the support and unconditional trust from Julidans and One Dance festivals, still having access to ICK studios at least for a period of time, the way Dirty Art alumni stepped in to help. I am very grateful. It’s just that we had to pull a lot of magic tricks and faced a lot of challenges: funding from different countries, delays due to political forces beyond our control. It’s still ongoing. But I am learning a lot.

– I know that you are not only directing but also producing the show. How do you manage to combine these activities?

I never gave it much thought. I was raised in the DIY scene in Sofia; my dad didn’t have a producer, his friends didn’t have producers, I didn’t think I was supposed to have a producer. I thought that’s for when you organize BIG events. My mom was doing production for events, but then again, she was also doing the marketing and other things, so I didn’t think production was a separate thing. Maybe it’s a Balkan mindset. Maybe lack of resources. Either way, I like doing it; it keeps the directing grounded.

– I heard that there was a moment when one of your performers was injured and you became the backup plan yourself. Do you still like to perform, or are you sailing more in the direction of directing?

I’ve gone through a lot of heartbreaks this year. I wanted to be not just off stage, but completely out of sight. My dance practice is my self-remedy, so I can never leave that behind. It’s just that being perceived is quite a violent process. You really need to be sure of who you are; otherwise it can completely shred you. I was in a very boundless state, I wasn’t ready. But I am a performer, not a director. At least not in the traditional sense. I am the glue to different processes and mediate between different people, but I don’t want the final say. It’s complete anarchy at the Anxiety Enterprises™ — and that’s how it should be.

– What are your thoughts on the Amsterdam art scene? How has being part of WOW Lieven shaped your artistic perspective or professional network?

It’s a love/hate thing. I really think the Amsterdam scene is unique in all the resources it offers artists, especially the structures set up to facilitate that. It’s such a privilege to be able to make things happen—things that are alternative, uncertain, experimental. But I feel the scene has lost touch with the history that made this possible—all the grassroots movements that fought for this openness of mind and pushed for the creation of these structures. Sometimes the scene feels shallow, and we have all contributed to that, whether voluntarily or not, by acting self-centered and profit-oriented. I think it’s gotten to the point where there’s so little collaboration that the scene is lowkey collapsing in on itself. I say that’s a good thing—it might push us to build something more sustainable.

I’m very new to WOW, but I’m already very grateful for the encounters and collaborations that have emerged in my short time here. It’s been a while since I’ve gone to knock on my neighbor’s door because I have an idea.

– Financial sustainability is a major concern for independent artists. How do you navigate this challenge while staying true to your political and artistic values?

I work a normal job on the side ♡ I don’t know why that’s a taboo for some.

I also try to have different sources of income. The more things you depend on, the less you depend on any one of them—if that makes sense. Showing old work, making new work, being involved in other artists’ projects—it’s a balancing act.

I’m still figuring out if being an artist aligns with my political views at all. I think if all the political events in the past few years haven’t made you radically question who you are and what you’re doing, then something’s wrong.

– You graduated from Sandberg. What has life been like after your studies? What have been the key challenges and opportunities—and how did your master’s experience prepare you for them?

For me, education is about deconstruction. Both SNDO and the Sandberg Design Department maybe haven’t directly prepared me for anything specific but have made me a better person. They pushed me out of my comfort zones, made me question my epistemic and aesthetic prejudices, exposed me to different points of view, and made me realize my shortcomings and blind spots.

I’m most thankful for what I’ve unlearned and for the space to be vulnerable—and to fail as many times as needed until I find a better way.

– What five elements do you consider essential for building a sustainable, long-term artistic practice—both creatively and practically?

- Your relationships with people.

- Your relationships with people.

- Your relationships with people.

- Your relationships with people.

- Your relationships with people.

– Where do you see yourself—artistically and personally—over the next few years? Do you follow a defined plan, or do you allow intuition to guide your path?

A combination. I like to dream ahead but try to remain sensitive and listen to the needs around me. Paradoxically, I see myself producing. There are many artists I admire, and I want to see their work get the resources and attention they deserve.

I’m researching how to make Trevoga into a kind of disembodied production house—finding ways to be more independent and create some stability that others could lean on too. Let’s see.

– How do you recharge creatively and emotionally?

Just some silence is usually enough.

– If you could be reincarnated as a plant or an animal, what would you choose—and why?

Ohhhh, I’d be like a monstera or a snake plant in a pot, with my roots threading around themselves in that claustrophobic space, and I’d just repeat to myself—well, at least I’m not outside where many things can happen to me.

Or I’d be one of those really easy-to-ragebait chihuahuas… or maybe that was my previous life.

Photos by Roman Ermolaev

by WOW